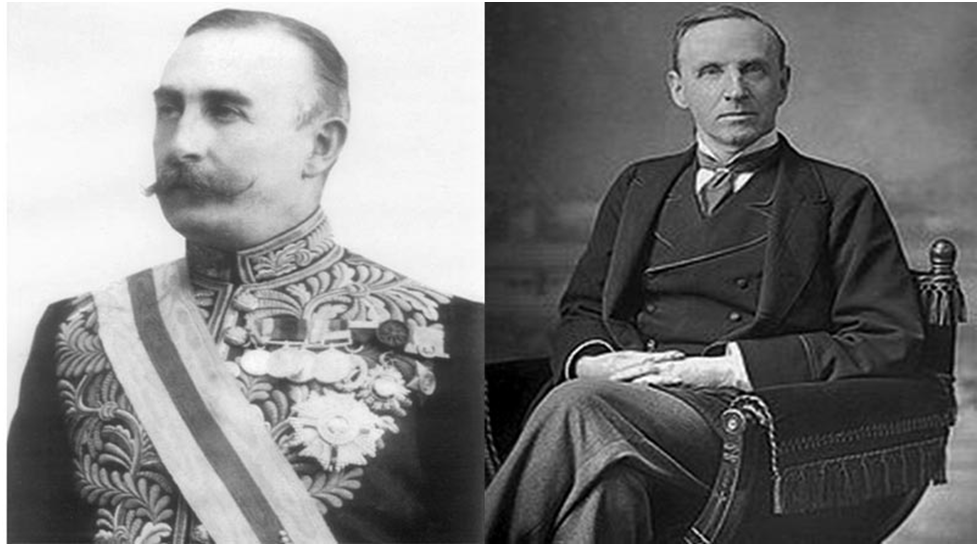

The Indian Councils Act of 1909 is also known as Morley-Minto Reforms (Lord Morley was the then Secretary of State for India and Lord Minto was the then Viceroy of India).

The features of this Act were as follows:

● The elective principle was recognised for the non official membership of the councils in India. Indians were allowed to participate in the election of various legislative councils, though on the basis of class and community.

● For the first time, separate electorates for Muslims for election to the central council was established—a most detrimental step for India.

● The number of elected members in the Imperial Legislative Council and the Provincial Legislative Councils was increased. In the provincial councils, non-official majority was introduced, but since some of these non-officials were nominated and not elected, the overall non-elected majority remained.

● In the Imperial Legislative Council, of the total 69 members, 37 were to be the officials and of the 32 non-officials, 5 were to be nominated. Of the 27 elected non-officials, 8 seats were reserved for the Muslims under separate electorates (only Muslims could vote here for the Muslim candidates), while 4 seats were reserved for the British capitalists, 2 for the landlords, and 13 seats came under general electorate.

● The elected members were to be indirectly elected. The local bodies were to elect an electoral college, which in turn would elect members of provincial legislatures, who, in turn, would elect members of the central legislature.

● Besides separate electorates for the Muslims, representation in excess of the strength of their population was accorded to the Muslims. Also, the income qualification for Muslim voters was kept lower than that for Hindus.

● Powers of legislatures—both at the centre and in provinces—were enlarged and the legislatures could now pass resolutions (which may or may not be accepted), ask questions and supplementaries, vote separate items in the budget though the budget as a whole could not be voted upon.

● One Indian was to be appointed to the viceroy’s executive council (Satyendra Sinha was the first Indian to be appointed in 1909).

Evaluation of Morley-Minto Reforms of 1909

֍ The reforms of 1909 afforded no answer to the Indian political problem.

֍ Lord Morley made it clear that colonial self-government (as demanded by the Congress) was not suitable for India, and he was against the introduction of parliamentary or responsible government in India.

֍ The ‘constitutional’ reforms were, in fact, aimed at dividing the nationalist ranks by confusing the Moderates and at checking the growth of unity among Indians through the obnoxious instrument of separate electorates.

֍ The government aimed at rallying the Moderates and the Muslims against the rising tide of nationalism.

֍ The officials and the Muslim leaders often talked of the entire community when they talked of the separate electorates, but in reality it meant the appeasement of just a small section of the Muslim elite.

֍ Besides, the system of election was too indirect and it gave the impression of “infiltration of legislators through a number of sieves”.

֍ And, while parliamentary forms were introduced, no responsibility was conceded, which sometimes

led to thoughtless and irresponsible criticism of the government. Only some members like Gokhale put to

constructive use the opportunity to debate in the councils by demanding universal primary education, attacking repressive policies, and drawing attention to the plight of indentured labour and Indian workers in South Africa.

֍ What the reforms of 1909 gave to the people of the country was a shadow rather than substance. The people had demanded self-government, but what they were given instead was ‘benevolent despotism’.

Must read: Government of India Act, 1919