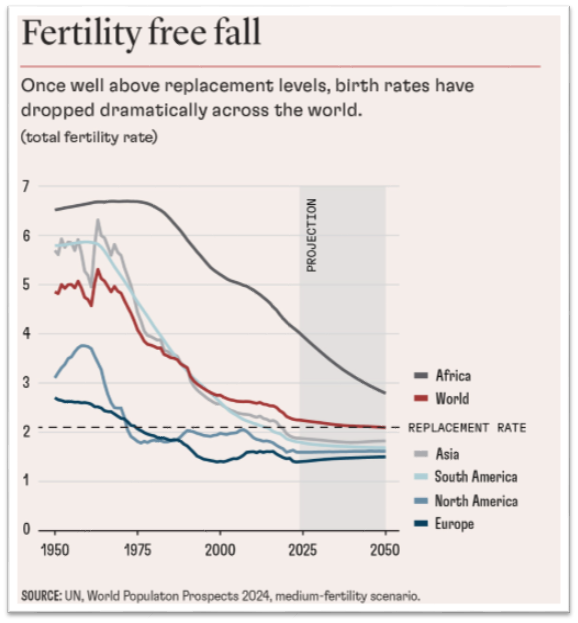

Today, most parts of the world are grappling with declining Total Fertility Rates (TFR), which is the average number of children a woman is likely to bear in her lifetime. Though global fertility rates have been falling for decades but have now reached historically low levels.

While the human population now exceeds 8 billion and may top 10 billion by 2050, the momentum of growth is dissipating because of declines in its most powerful driver—fertility. Over the next 25 years, East Asia, Europe, and Russia will experience significant population declines.

The Global Burden of Disease, Injuries and Risk Factors Study (GBD)-2021 estimated that globally, TFR more than halved from around 5 in 1950 to 2.2 in 2021.

Which countries have to face the greatest population loss in the coming decades?

Population loss in the coming quarter century will be largest in China with a drop of 155.8 million, Japan with 18 million, Russia with 7.9 million, Italy with 7.3 million, Ukraine with 7 million, and South Korea with 6.5 million (Chart 2). In relative terms, average annual rates of population decline will be highest at 0.9 percent in Moldova and in Bosnia and Herzegovina; 0.8 percent in Albania, Bulgaria, and Lithuania; and 0.7 percent in Latvia and Ukraine.

Which regions of the world still have high TFR?

The only major region in the world with a high TFR today is sub-Saharan Africa, where medical advances have reduced child mortality, but fertility remains high due to cultural reasons, poverty, and the lack of decision-making powers for women.

Africa and a number of low-income countries on other continents have fertility rates still at 4 or higher. As head counts elsewhere dwindle, Africa’s share of global population is likely to increase from 19 percent in 2025 to 26 percent in 2050.

Advantages and Benefits of Declining Fertility Rates

Fewer children and smaller populations will mean less need for spending on housing and childcare, freeing resources for other uses such as research and development and adoption of advanced technologies.

This signals better education and financial independence for more women, and greater participation in making reproductive choices.

Infant mortality rates have come down drastically, women are living increasingly healthier lives, and couples are able to give their children a higher quality of life.

Declines in fertility rates can stimulate economic growth by spurring expanded labor force participation, increased savings, and more accumulation of physical and human capital.

Population decline may also enhance social welfare if it reduces environmental pressures such as land, air, and water pollution; climate change; deforestation; and the loss of biodiversity.

Disadvantages and Drawbacks of Declining Fertility Rates

An extremely low TFR can have long-term consequences for societies:

It could hinder economic progress as there will be fewer workers leading to shortages of labour, scientists, and innovators. This could lead to a paucity of new ideas and long-term economic stagnation.

Moreover, as populations shrink, the proportion of older people tends to expand, weighing on economies and challenging the sustainability of social safety nets and pensions.

Increasingly unsustainable proportions of people in the above-60 age group and a shrinking of the working-age (15-59 years) population leads to higher dependency ratios, higher taxation to fund the cost of healthcare for the large numbers of the elderly, and changes in social structures and relationships.

A nation’s slow or negative population growth relative to other countries may translate into less military might and political clout on the world stage. For example, some historians attribute France’s 1871 defeat in the Franco-Prussian War to the low fertility and slow rate of population growth that stemmed from early and widespread use of contraception among married couples in France.

What are the Reasons Behind Declining Fertility Rates in India?

India’s lowered TFR is the result of decades of government investment in family planning, changing social attitudes about family sizes, rising costs of raising children, and improvements in the education of women.

India’s overall TFR stood at 1.91 in 2021. This is less than the ‘replacement level’ of 2.1, or the number of children that a woman would need to have to replace herself and her partner in the next generation. This figure assumes there will be no in- or out-migration, which is not the case in reality.

Hundreds of millions of people are not able to have the number of children they want, citing the prohibitive cost of parenthood and the lack of a suitable partner as some of the reasons.

Reasons Identified by Peter McDonald for the Global Decline in TFRs

In 2006, demographer Peter McDonald identified two reasons for the decline in TFRs.

One, rising social liberalism, in which individuals in modern societies were re-examining social norms and institutions, and increasingly focusing on individual aspirations.

Two, the withdrawal of the welfare state in major Western economies in the 1980s and 1990s, which led to “loss of trust in others, loss of a sense of the value of service (altruism), decline of community…and fear of failure or of being left behind”.

Both processes deprioritised having children as a mandate for living a good life, McDonald concluded.

“The solution to low fertility…lies in providing a greater sense of assurance to young women and young men that, if they marry and have children, they will be supported by the society in this socially and individually important decision,” he wrote.

McDonald also argued that incentivising policies have failed in countries like Japan and Singapore because they targeted particular types of women (like high earners) rather than reforming societal institutions.

Are falling birth rates really bad?

There is nothing intrinsically wrong with an economy expanding or shrinking along with its population. It’s possible that falling birth rates are a clear expression of societal preferences that we should simply accept. The problems have to do with the side effects, such as declining per capita GDP, stagnating innovation and growth, and the challenges of supporting an aging population.

Can Subsidies and Tax Credits help in Controlling the Declining Fertility Rates?

As countries around the world grapple with declining fertility rates, many, like China, have introduced subsidies and tax incentives to encourage couples to have more children.

One reason for this is the understanding that the rising cost of living is a major deterrent to parenthood. Almost 4 in 10 respondents in an online survey of more than 14,000 adults in 14 countries carried out by the United Nations Population Fund and YouGov in June,2025, said financial limitations were stopping them from having the families they wanted.

However, these measures have had only a limited impact. The think tank Center for Strategic and International Studies noted in a 2023 article that “Representative studies on the expansion of financial assistance show that the effects are positive but limited.” The article cited a 2013 study that reported that child allowances, even if doubled, lead to the probability of childbirth increasing by only 19.2%.

What can be done to Address Declining Fertility Rates?

Policymakers could deploy a range of family-friendly policies to encourage increased fertility, although more children create economic strains of their own, and an expanded workforce would take two decades to materialize. Such policies could seek to enable a better balance between work and family responsibilities. They might include tax breaks for larger families, extended and more flexible parental leave policies, public or subsidized private childcare, and subsidies for infertility treatment.

Supporting childbirth requires a comprehensive policy package, including financial support, parental leave, and cultural measures. Childcare subsidies should work in tandem with related policies regarding childcare, education, employment, taxation and housing.

Clearly, policymakers face crucial choices in managing the unfolding demographic trends. Responses may include measures to encourage fertility, adjustments to migration policies, expansion of education, and efforts to encourage innovation. Together with advances in digitalization, automation, and artificial intelligence, the coming declines in population pose a significant challenge but also a potential opportunity for the world’s economies.