QUES . Examine the evolving pattern of Centre-State financial relations in the context of planned development in India. How far have the recent reforms impacted the fiscal federalism in India? Answer in 250 words.15 marks. UPSC MAINS 2025 GS PAPER 2

HINTS:

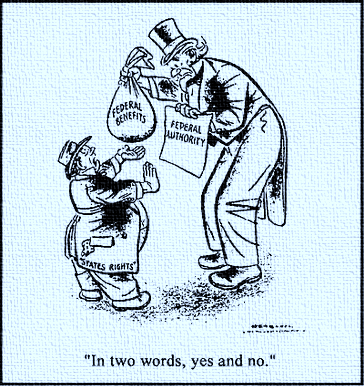

Indian Constitution is often described as “quasi-federal,” and the financial relations between Centre and States testify it. There has been signs of Central dominance with state dependence along with financial autonomy to States evolving over time.

Must read: Issues and Challenges in Centre-State Financial Relations and Fiscal Federalism

Evolving Pattern of Centre-State Financial Relations in the Context of Planned Development in India

The Centre-State financial relations in India have evolved significantly in the context of planned development, moving from a highly centralized model to one emphasizing cooperative federalism.

Centralized Planning Era (1950-1991)

Dominance of Planning Commission:

Financial relations were largely dictated by the Five-Year Plans which allocated resources through discretionary grants and loans. The Planning Commission played a key role in allocating Central Plan Assistance and Special Category Status to states, influencing states’ developmental budgets and national scheme funding. The Planning Commission controlled plan grants and project approvals, often bypassing Finance Commissions.

Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS):

Centrally sponsored schemes became dominant instruments for social development. States had to implement national programs by contributing matching funds, which led to a “transfer dependency syndrome” and limited their ability to address unique local needs. It eroded state autonomy due to conditional funding.

Vertical Fiscal Imbalance:

The Centre held more revenue-generating powers, while states had significant expenditure responsibilities, creating a fiscal imbalance where States were heavily dependent on the Centre for financial transfers via Five-Year Plans and Centrally Sponsored Schemes.

Planning Under Liberalisation (Post-1991)

Increased State Autonomy:

Economic reforms reduced the Centre’s direct involvement in planning, allowing states more autonomy in attracting private and foreign investment.

Increased Role of Finance Commissions:

The subsequent Finance Commissions significantly increased the states’ share in the divisible pool of central taxes, providing more untied funds and strengthening fiscal autonomy. Horizontal devolution among states now considers various criteria, including income distance, demographic performance, and tax efforts.

Focus on Fiscal Responsibility:

The Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act encouraged greater fiscal discipline at the state level.

Towards Cooperative Federalism (Post-2014)

Abolition of the Planning Commission:

The Planning Commission’s role in financial allocation was replaced by the advisory NITI Aayog in 2014 ending centralized plan transfers and shifting to Finance Commission-led devolution. With the abolition of the Planning Commission, Finance Commissions became the sole constitutional mechanism for transfers. The creation of NITI Aayog promoted cooperative and competitive federalism, though NITI Aayog lacks the financial allocation powers of its predecessor.

Introduction of GST:

The GST Council fostered cooperative federalism through consensus-based decision-making. However, the centralization of tax powers and concerns about revenue shortfalls and the sharing of GST revenue have reduced state autonomy.

Recent Reforms in Fiscal Federalism in India

Increased Tax Devolution:

The 14th Finance Commission significantly raised states’ share of the central government’s divisible tax pool from 32% to 42%, boosting fiscal autonomy of the states.

Goods and Services Tax (GST):

The implementation of GST and the establishment of the GST Council have aimed to create a unified indirect tax regime through cooperative decision-making between the Centre and states.

Abolition of Planning Commission:

The dissolution of the Planning Commission and the creation of NITI Aayog have shifted the focus from centralized planning to more cooperative and rules-based fiscal transfers.

15th Finance Commission’s Horizontal Distribution:

The 15th Finance Commission refined the criteria for allocating funds among states, incorporating factors like income distance, population (using 2011 census data), area, and demographic performance to address regional disparities.

How far have the recent reforms impacted the fiscal federalism in India?

Positive impacts of recent reforms on fiscal federalism in India

Greater devolution of funds to States:

The 14th Finance Commission’s recommendations transformed India’s fiscal landscape by increasing the states’ share of central taxes to 42%, providing flexibility to the states in social spending and empowering them with greater financial autonomy.

Performance based grants:

The 15th Finance Commission introduced performance-based incentives by linking grants with outcomes. This may encourage states to pursue reforms in health, education, etc.

More rationalisation and less discretion in plan transfers:

The abolition of Planning Commission (2014) and establishment of NITI Aayog has reduced discretionary plan grants and thus enhancing predictability in transfers.

Promotion of cooperative federalism with consensual decision-making:

The abolition of Planning Commission (2014) and establishment of NITI Aayog marked a shift from “command-and-control” to “collaborate-and-compete” federalism. Moreover, GST Council is proving to be a model of cooperative decision-making where Union and States decide taxation together.

Negative impacts of recent reforms on fiscal federalism in India

Issues with GST reforms:

Under GST reforms, states surrendered taxation autonomy. However, uncertainty in GST revenue sharing, revenue losses for states, and delays in compensation payments have caused friction between the Centre and States.

However, compensation mechanism disputes (Kerala, Punjab cases) exposed structural tensions. GST compensation delay created mistrust.

Issues with Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS):

Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS) criteria continues on 28 schemes, thus Centre maintaining conditional transfers. Moreover, Centre is retaining discretion in CSS design & tied grants.

Borrowing restrictions on States:

Borrowing restrictions under Article 293 of the Constitution limit state fiscal flexibility during crises. For example, the state needs the consent of the Government of India in some types of loans.

Cess & surcharges not shareable with states:

Cesses and surcharges bypass divisible pool. However, they increased from 10.4% (2010-11) to 20.7% (2020-21) of gross tax revenue.

Vertical fiscal imbalance:

States have greater expenditure responsibilities than their revenue collection capacity, leading to dependence on central transfers.

Conditional Transfers and Central Dominance:

The proportion of conditional grants to states continues to grow, tying their spending to the Centre’s priorities and reducing the State autonomy in expenditure planning.

Conclusion:

While reforms enhanced fiscal autonomy, issues such as the Centre’s increasing use of cesses and surcharges, borrowing restrictions on States and horizontal fiscal imbalances remain a challenge. Such issues need to be addressed but not at the cost of Centre’s control over the States as true fiscal federalism lies in ensuring both national integration and state autonomy.